The Torque Decay Crisis: 6 Myths Killing Your Hinge Reliability

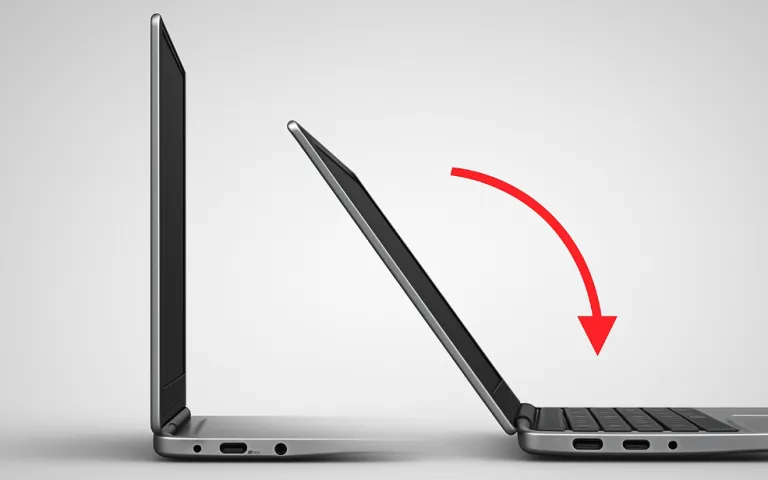

In precision mechanical design, there is nothing more frustrating than this scenario: your tolerance calculations are flawless and the prototype passed 20,000 cycles, yet six months after shipping, you are hit with a wave of returns due to Hinge Torque Decay, damping failure, and “screen wobble.”

If you view this decay merely as a surface wear issue, you have already lost the battle. This article draws on tribology and material physics to dismantle 6 common engineering myths and expose the true culprits behind high-performance hinge failure.

As Long as Material “Yield Strength” is High, the Spring Won’t Relax

[The Engineering Truth]: Stress Relaxation is not about strength; it is about micro-dislocations.

Many engineers default to SUS301 (Full Hard), believing its 1000MPa+ tensile strength is sufficient to maintain spring force. However, strength resists “fracture,” not “relaxation.”

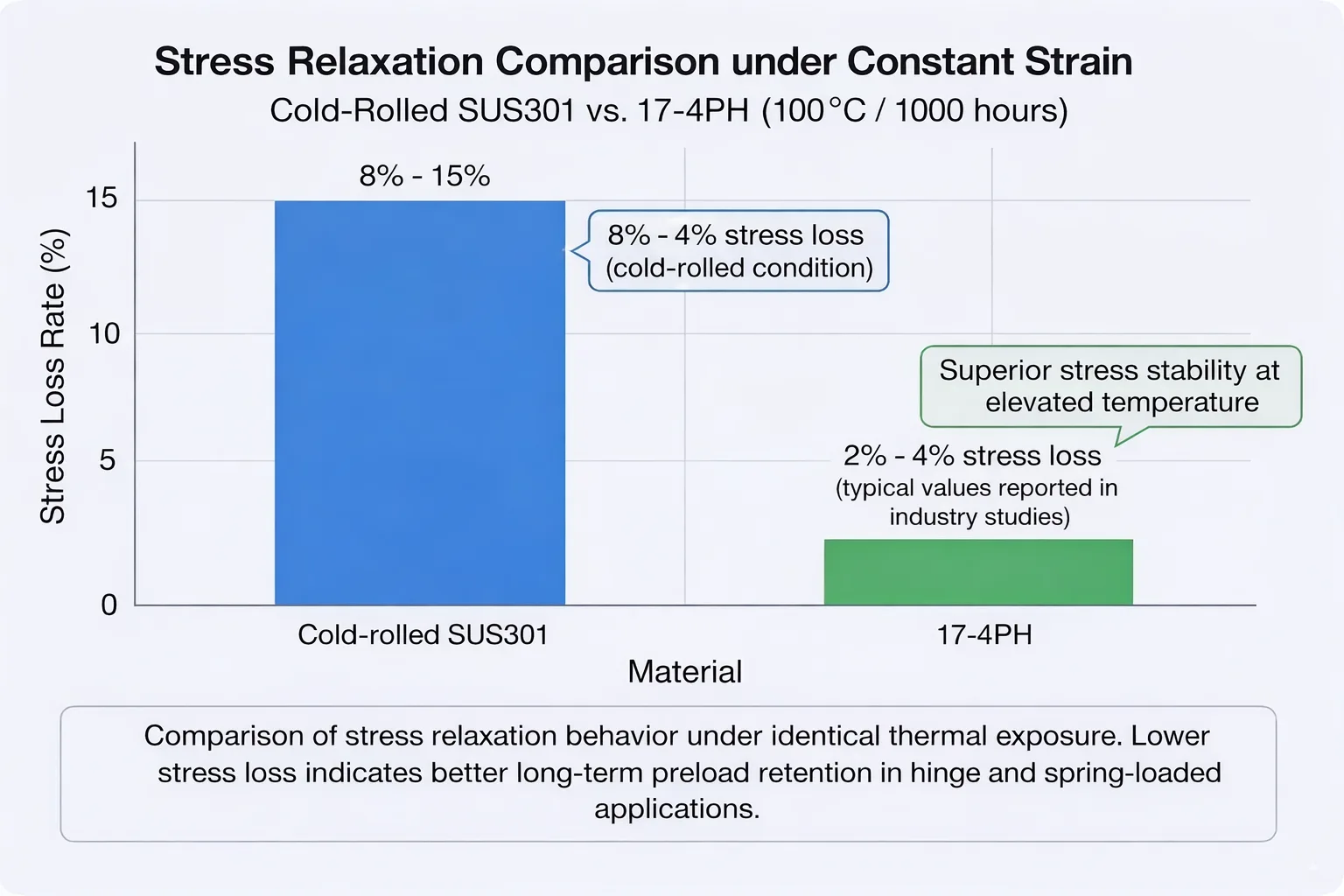

- The Deep Mechanism: The high strength of SUS301 comes from high-density dislocations introduced during cold working. Under stress (especially when temperatures exceed 50°C), these dislocations are prone to thermally activated recovery. Data shows that cold-rolled SUS301 operating at 100°C for 1000 hours can suffer a stress loss rate of 8%-15%. This means your interference fit hasn’t changed, but the normal force has simply vanished.

- The Correct Strategy: For medical or military-grade applications, you must abandon SUS301 in favor of 17-4PH (H1150) precipitation-hardening stainless steel. Its copper-rich precipitates effectively “pin” dislocation movement, controlling the relaxation rate to within 3% under the same conditions.

To Minimize Wear, the Shaft Surface Must Be Mirror-Smooth (Ra < 0.2µm)

[The Engineering Truth]: A mirror finish is a “lubricant killer” and causes severe Stick-Slip effects.

Intuition tells us that rougher surfaces cause more wear. Consequently, many drawings specify a mirror finish of Ra 0.1.

- The Deep Mechanism:

- Reservoir Failure: An overly smooth surface lacks the microscopic valleys needed to store grease. Under pressure, the grease is rapidly squeezed out, leading to boundary lubrication (dry friction).

- Stiction: Extremely high intermolecular forces lead to a massive spike in start-up torque (Stiction), resulting in a “sticky” or jerky feel for the user.

- The Correct Strategy: Follow the “Golden Roughness” rule of tribology. Control the shaft surface between Ra 0.4 – 0.8 µm. We specifically recommend Centerless Grinding (which creates circumferential textures) over turning. This roughness range acts as a micro-oil reservoir and hits the optimal balance point of the Archard Wear Equation.

Grease is Just for “Lubrication,” Any High-Temp Grease Will Do

[The Engineering Truth]: In damping hinges, grease is a “structural component” that generates torque. Oil bleeding equals failure.

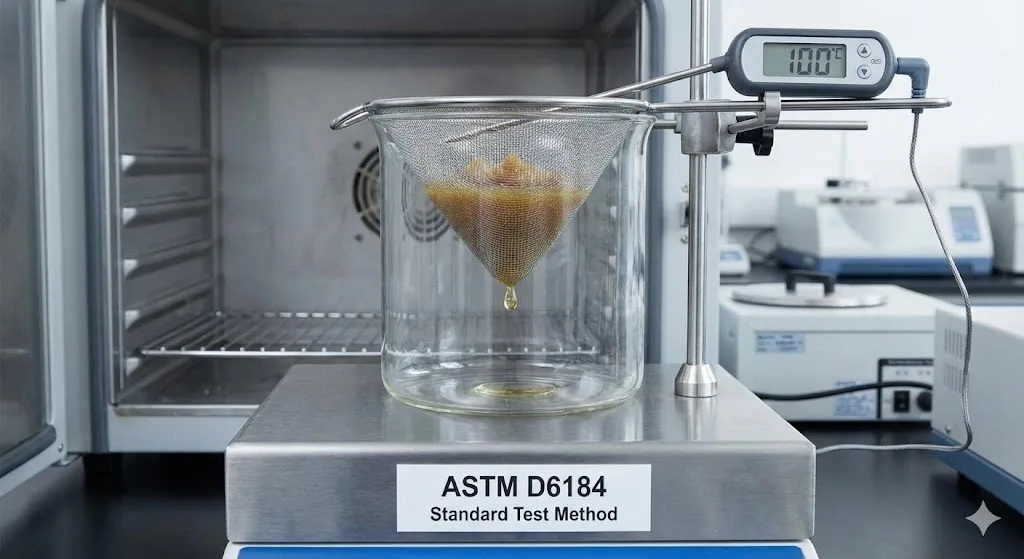

Many failure analyses show zero wear inside the hinge, yet torque has dropped to zero. Disassembly reveals only dry, caked powder.

- The Deep Mechanism: Under centrifugal force or long-term stagnation, the base oil of ordinary lithium grease separates from the thickener (Bleeding). Once the base oil flows away from the friction zone, the remaining thickener becomes an abrasive agent.

- The Correct Strategy:

- Reject generic grease. Set strict ASTM D6184 acceptance standards (Oil Separation < 1% @ 24h/100°C).

- For high-end projects, specify PFPE (Perfluoropolyether) damping grease. While costly, its extremely low surface tension and oxidation resistance are the only way to guarantee a 5+ year lifespan.

Thermal Expansion is Temporary; Torque Will Recover at Room Temperature

[The Engineering Truth]: When CTE Mismatch meets High Stress, “Thermal Ratcheting” occurs, causing permanent expansion.

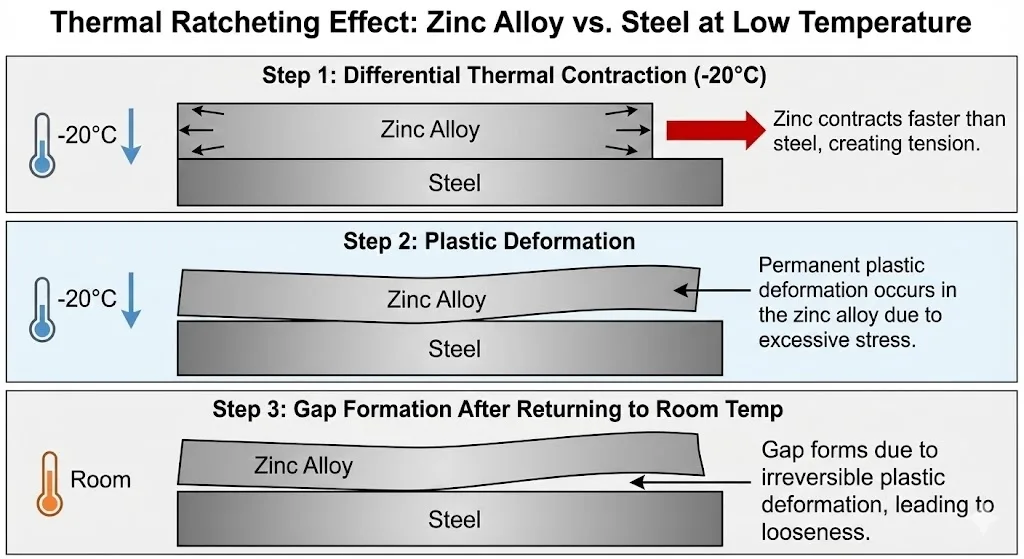

When a steel shaft (CTE ~16) is mated with a Zinc alloy die-cast housing (CTE ~27):

- The Low-Temp Disaster (-20°C): Zinc contracts faster than steel, causing the interference fit to skyrocket. If the resulting hoop stress exceeds the zinc alloy’s yield limit, the housing gets “stretched” (plastic deformation).

- The Result: When the temperature returns to room level, the shaft returns to its original size, but the housing is now permanently larger. The interference is lost, and torque suffers irreversible decay.

- The Correct Strategy: You must perform MIL-STD-810H Method 503.7 Thermal Shock testing. Design-wise, aim for similar materials, or introduce a high-elasticity steel Spring Clip to absorb thermal deformation rather than relying on a rigid die-cast bore.

A ±0.02mm Tolerance Ensures Batch Consistency

[The Engineering Truth]: Linear tolerance stacking is a fallacy here; torque sensitivity to dimension is non-linear.

In micro-hinges, a deviation of ±0.02mm at the edge of the tolerance band can cause torque fluctuations of ±40%.

- The Deep Mechanism:

- False High Torque: Products on the tight end of the tolerance have high initial torque, but this is often because the spring is in an overloaded state. These units will suffer “cliff-like” decay within the first 500 cycles as surface asperities are sheared off.

- Process Capability: Simple Pass/Fail checks cannot filter out these “early death” products.

- The Correct Strategy:

- Implement Statistical Process Control (SPC) with Cpk > 1.33.

- Implement Match Machining: Grade shafts and holes by actual size (Pairing A with A, B with B) to artificially reduce the variation range of the fit gap.

If It Doesn’t Break, It Passes the Fatigue Test

[The Engineering Truth]: Stiffness Degradation hits earlier and more covertly than fracture.

Referencing the Dell Inspiron Hinge Failure case, many failures do not start with a snap, but with “looseness.”

- The Deep Mechanism: According to the S-N curve, even if stress doesn’t reach the fracture point, the initiation of micro-cracks reduces the effective cross-section of the material, leading to a drop in stiffness. Per Hooke’s Law, a drop in stiffness directly reduces normal force, and torque decays accordingly.

- The Correct Strategy: Testing shouldn’t just look at the finish line. Require Full Lifecycle Torque Monitoring to plot decay curves. The standard for passing isn’t “it didn’t break,” but “Dynamic Torque Decay < 20% after 20,000 cycles.”

FAQ

Q1: Switching from SUS301 to 17-4PH and generic grease to PFPE increases costs by 3-5x. My boss won’t approve it. What do I do?

A: Persuade them using “Total Cost of Ownership (TCO)” rather than “BOM Cost.” While the unit cost rises by a few dollars, for medical devices or rugged terminals selling for thousands, the RMA cost (Return Merchandise Authorization) of a hinge failure is often 100x higher than the BOM difference. Crucially, using cheap materials (SUS301) usually requires designing a larger initial interference to offset expected decay, which actually increases assembly difficulty and defect rates. High-performance materials allow for “First Time Right” yields, which saves money in manufacturing.

Q2: If existing products are already showing torque decay, can I re-tighten the nut to restore life?

A: No, that is a stopgap measure that will backfire. If the decay is caused by grease loss (dry friction) or severe abrasive wear, simply increasing the normal force (tightening the nut) will cause contact stress to skyrocket. This accelerates the wear of the remaining material, leading to a complete seizure (lock-up) within a few hundred cycles.

Q3: To shorten the test cycle, can I use a motor to test lifespan at 60 RPM?

A: Absolutely forbidden. This is the most common invalid test. Human opening/closing speed is typically only 5-10 RPM. Increasing speed to 60 RPM causes Frictional Heating. Because hinges have low thermal mass, heat cannot dissipate, causing the grease viscosity to drop instantly or even carbonize, leading to false failures that wouldn’t happen in real use.

Q4: Since torque decay is inevitable, should I design with a 50% Safety Factor (extra torque)?

A: This is a dangerous myth. If you are using materials prone to relaxation (like SUS301 in Myth 1), adding 50% initial torque means adding 50% initial stress. According to the Arrhenius equation, higher stress accelerates the rate of stress relaxation exponentially. You are simply speeding up the failure.

Conclusion

Torque decay is not black magic; it is a complex interplay of materials science, tribology, and manufacturing processes. As engineers, when we stop staring at simple dimensional tolerances and start focusing on Dislocation Stability (17-4PH), Micro-topography (Ra/QPQ), and Rheological Properties (PFPE), only then can we design high-end mechanisms that retain that “silky smooth” feel even after years of use.